What prospects for Europe and the Serbian world in the new geopolitical configuration triggered by the conflict in Ukraine?

Introduction

The crisis in Ukraine has led to a reconfiguration of the European and world geopolitical order, which does not favour the European Union, because it is still defending the unipolar order promoted by Washington and is therefore drifting towards a process of geopolitical subjugation.

Although the EU’s posture is obsolete to enhance strategic independence for its member states, Europeans still need an alliance in the multipolar world. However, the EU is no longer the appropriate platform in the context of great power rivalry because it is positioned as a periphery of the Euro-Atlantic area and not as a geopolitical centre.

A reform of the European project would be necessary to protect the interests and sovereignty and improve the geopolitical positioning of its member states, although it is doubtful it would succeed through the EU because of its increasing internal fragmentation and increasing vassalization to Washington: NATO.

In this context of geopolitical upheavals, the Serbian world, long ostracized by both the EU and NATO, needs to reposition itself on the map of Europe and be recognised as an identifiable player by the other powers, so that it can in the future participate in the new concert of European nations.

The problematic of this article is approached according to the geopolitical angle. Geopolitics is the study of power rivalries over territories and of their populations, in different spaces (in land, sea and air spaces, but also in space, cyberspace, digital space and the space-time of artificial intelligence) at global, continental, national, regional, and local scales[1]. There are two complementary modes of geopolitics: geopolitics as a method of analysis, and geopolitics as a strategy (Thomann, 2013). However, before constructing a geopolitical strategy, it is necessary to make a clinical diagnosis of the situation. This involves identifying the geopolitical stakes and strategies of the rival actors in the different spaces of confrontation as well as interpreting the explicit and implicit geopolitical interests. Geopolitics and cartography are inseparable because both space and territory need to be represented in order to achieve understanding.

Global geopolitical diagnosis

The conflict in Ukraine reinforces the thesis that the new geopolitical configuration on a global scale is characterised by a struggle for the distribution of geopolitical spaces between major powers. On a global scale, this conflict is part of the clarification, by means of military but also geo-economic tools, of the global geopolitical balance and its new configuration in the 21st century dominated by three main poles, the United States, China, and Russia, and in Europe the geopolitical rivalry between the United States and Russia. Following the transformation of the spatial order resulting from the crisis in Ukraine, a new balance of power is emerging in the world, characterised by the re-emergence of Russia and the rise of China, causing the fragmentation of the old unipolar spatial order.

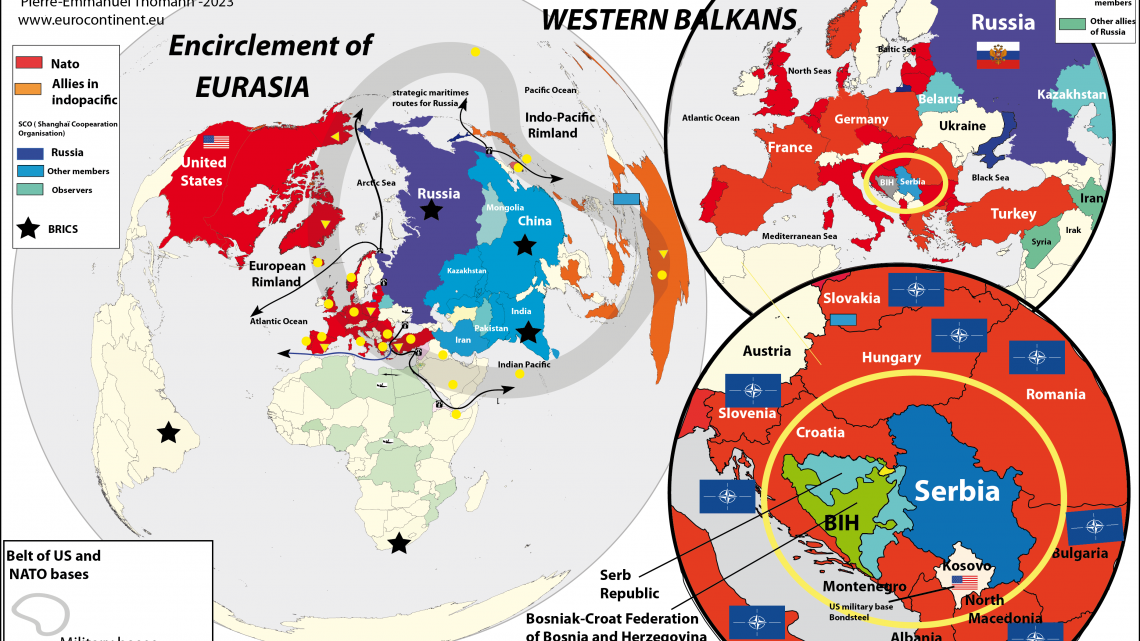

The global configuration and in particular the geopolitical posture of the United States has the greatest impact on Europeans. With remarkable consistency, the United States seeks to prevent the emergence of a power that could challenge its status as a world power on the Eurasian continent. This geopolitical constant, the Wolfowitz doctrine, was re-emphasised at the end of the Cold War in 1992 (New York Times 1992). The ambition is to preserve the global leadership of the United States and to slow down the emergence of a multipolar world (Foucher Michel 2011) in the context of great power rivalry (map 1: Geopolitical strategy of United States against Russia in the increasing multipolar context). The aim of the United States is to stand up to Russia and control the Rimland (according to Spykman’s geopolitical doctrine)[2] but also to fragment Eurasia (according to Mackinder’s doctrine) and detach Ukraine from Russia (Brzezinski doctrine[3]).

The United States and its NATO allies, who make up the West, have exercised supremacy in the depths of the European continent since the demise of the USSR, with successive enlargements of NATO. The Russian army’s special military operation is above all the consequence of NATO and its military bases moving closer to Russia’s borders with the aim of encirclement. This development has of course been perceived as a threat by Russia, which is seeking to rebalance geopolitical forces. Russia’s strategic stance is also an extension of the long European tradition of the balance of power and as « the balance of power in the world has been upset » (Putin 2022), Moscow felt that it had to be re-established. This crisis is also the consequence, linked to the previous one, of Washington’s refusal (Arms Control Association 2022) to negotiate a new European security architecture proposed by Moscow in 2021 (The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation 2021), with the main demand being a halt to NATO enlargement[4].

It is a geopolitical error of judgement to believe that Moscow would not at some point react to the expansion of the United States and NATO over the long term, especially as the Russia-Georgia war demonstrated that NATO enlargement was a red line for Moscow (Thomann, 2008). In 1997, the man who designed the policy of containing the USSR during the Cold War, George Kennan (Kennan, 1997), like many other experts (Los Angeles Times. 1997)[5], warned that « NATO enlargement would be the most fatal mistake in American policy in the entire post-Cold War era » (Map 2: Ukraine conflict: a consequence of NATO expansion).

The decisive battle for world order that is taking place in Ukraine has largely been provoked by Washington, which is pursuing its geopolitical strategy of fragmenting the Russian world (with a fratricidal war between Moscow and Kiev) but also Europe, in order to torpedo any potential European or Eurasian agreement on a Paris-Berlin-Moscow axis extended towards Beijing, and to pursue its grand strategy of encircling Eurasia against Russia and China. By waging a proxy war in support of the Kiev regime against Moscow (Washington Post, 2023) , the aim is to preserve Washington’s supremacy in Europe and the world, since an alliance between Germany, France and Russia would be able to counterbalance the United States and its loyal second-in-command the United Kingdom. With remarkable continuity, the United States seeks to prevent the emergence of a power that could challenge its status as a world power on the Eurasian continent. This geopolitical constant, the Wolfowitz Doctrine, was re-emphasised at the end of the Cold War in 1992 (Tyler 1992). The vision of « Euramerica from Vancouver to Kiev » has been imposed as opposed to the « Europe from Brest to Vladivostok » that General de Gaulle had anticipated (he spoke of « Europe from the Atlantic to the Urals »).

General de Gaulle’s strategic vision (1958-1969) was to create a « European Europe », i.e. a Europe of nations, rejecting the logic of blocs and gaining independence from the United States, based on a Franco-German core, but without unravelling the Atlantic Alliance. He also anticipated a « Europe from the Atlantic to the Urals » once Russia had emerged from communism. As long as the USSR remained the main threat, France had to remain in the Atlantic Alliance, but without military integration into NATO, and while preserving France’s independence and sovereignty, particularly with nuclear weapons. When he felt it was necessary, he also maintained a balance between the United States and the USSR, in order to widen France’s room for manoeuvre.

It would be difficult for the United States to wage a conflict on two fronts against Russia and China, which have been designated as its adversaries (The White House 2022). It is therefore in their interest to prolong the conflict and make Russia the enemy of the European member states of NATO and the EU, so as not to overextend their manoeuvre to encircle Eurasia. Hence the torpedoing of negotiations between Kiev and Moscow in March 2022 according to President Vladimir Putin (Tass 2023)

In view of the massive financial and military aid provided by Washington to Kiev, which far exceeds that of other contributors (Masters J, Merrow W. 2023), everything seems to indicate that Washington considers Russia (even if opinions differ) the most serious threat because Moscow challenges American hegemony in Europe, its last remaining exclusive zone of influence in the world. Moscow is proposing a European and Eurasian civilisational model as an alternative to the Americanised West, in phase with the multipolar world (Putin 2022). However, China cannot allow Russia to lose this conflict, nor can it allow Washington to accelerate its geopolitical encirclement, as it would end up caught between an expanding Euro-Atlantic front in Eurasia and the Indo-Pacific front.

On a global scale, however, since the launch of its military intervention in Ukraine in February 2022, Russia has made the most significant geopolitical gain by accelerating a shift in alliances towards a more multicentric world, definitively calling into question the unipolar vision of Washington and its close allies. Indeed, most Eurasian, African and Latin American states are refusing to align themselves with the « collective West » in a geo-economic war against Russia (map 3: Sanctions against Russia after its military operation in Ukraine, Rise of Eurasian globalization). This has also led to the weakening of multilateral institutions, which are incapable of applying international law because it is subject to contradictory and unilateral interpretations. To sum up, since 1991, when the USSR came to an end, we have moved from a bipolar to a unipolar and finally a multipolar configuration.

The EU as a geopolitical periphery

The distribution of power within the Euro-Atlantic geopolitical order, on the other hand, is increasingly hierarchical in favour of the United States. If we look at a world map, only the EU is aligned with the United States when it comes to sanctions against Russia (map 3: Sanctions against Russia after its military operation in Ukraine, Rise of Eurasian globalization). By deciding to deliver arms to Ukraine in synergy with NATO and in co-belligerence with Ukraine, without a clear strategy and without identifying common geopolitical interests independently among Europeans, this means a geopolitical subjugation of the EU Member States to the United States, the opposite of strategic independence. As long as the EU sees itself as complementary to NATO, it reinforces its marginalisation and its status as a periphery of the Euro-Atlantic area. Following in the footsteps of Washington and NATO, with its support for Kiev against Moscow, the EU is being transformed into a second front line under NATO leadership, with the United States manoeuvring behind Ukraine against Russia.

The President of the European Commission, Ursula Von der Leyen (Von der Leyen 2019) stressed in 2019 that Europe needed a geopolitical commission. In reality, the European Union is merely positioning itself as an instrument of Washington’s geopolitical strategy. From the geopolitical angle, the EU does not object to being a Rimland, the theatre of operations for Washington’s great manoeuvre to encircle Eurasia (Brzezinski, 1997, Florian L. 2014, Mitchell, 2018 )[6]. Since the EU rejects [7]

the model of a multicentric world (European Parliament 2019), de facto, under the guise of promoting multilateralism, it is in favour of a unipolar order dominated by the West.

In the European Parliament’s resolution of 12 March 2019 on the state of political relations between the European Union and Russia, it is stated that « Considering that Russia’s polycentric vision of the concert of powers contradicts the Union’s belief in multilateralism and a rules-based international order; that Russia’s adherence to and support for a rules-based multilateral order would create the conditions for a strengthening of relations with the Union. »

The West is a geopolitical representation that stems from the Cold War and the unipolar period that followed the demise of the USSR and refers to the states that make up the Atlantic alliance with the United States as its leader. The EU is aligning itself de facto with Washington’s geopolitical priorities, seeing Russia as a strategic challenge and China as a systemic challenge (European Council, 2022). The apparent unity within the European Union is merely a sign of its subservience to the United States and NATO, the ultimate stage in the Americanisation of Europe through its lack of an independent geopolitical strategy. The European Union’s new strategic compass (European Council, 2022) is merely a subset of the strategy of the United States and NATO in Europe. The Europeans of the EU thus become the adjustment variable of world geopolitics, because EU Member States do not identify their own common geopolitical priorities separate from Washington’s geopolitical priorities, particularly regarding Russia. The EU, driven by growing internal divisions – between southern and northern Europe on economic issues, between eastern and western Europe on values and migration, Brexit – has found a convenient enemy in Russia to mask its growing internal geopolitical fragmentation and its marginalisation in the great power rivalry. The objectives to be achieved by supporting Ukraine, whether to contain or, for the most ambitious, to break up Russia into several states (European Conservatives and Reformist Group 2023), are the subject of disagreement between the Member States.

According to this scenario, the European nations will be placed under the guardianship of a Euro-Atlanticist bloc exclusively dependent on flowsto the United States and cut off from links with Russia, perhaps soon even China. Washington is putting increasing pressure on the EU to impose sanctions against China. This situation is distracting the EU from the real jihadist threat in the South and from the challenges posed by migratory pressures. However, this drift did not start with the crisis in Ukraine, but with the Balkan wars in the 1990s.

.

The Balkan wars, a field of manoeuvre for the unipolar spatial order challenged by the war in Ukraine

The process of NATOisation of the EU, i.e., the European project under the cross-control of Washington by virtue of its complementarity with NATO, actually began with the wars in Yugoslavia and NATO’s military operations in Bosnia-Herzegovina (1995) and Kosovo (1999). These first military operations in NATO’s history constituted a geopolitical laboratory for the unipolar order project of Washington and its allies, Berlin in particular. This unipolar spatial order has today reached its limit with the crisis in Ukraine.

In Yugoslavia, the capitals of the external powers responsible for aggravating the crisis and escalating the conflict in accordance with their geopolitical interests were Berlin and Washington. Paris, because of the geopolitical priority given to the Franco-German couple in the negotiation of the Maastricht Treaty, did not reactivate its historic alliance with Serbia as in the First World War, and aligned itself with German American priorities (Gallois 2011), while the United Kingdom did the same because of its special relationship with the United States. Russia, weakened following the dissolution of the USSR, was unable to oppose the priorities of Berlin and Washington and their instrument NATO.

Ideologies change but geopolitical tropisms remain. As far as the Balkans are concerned, the Germans’ objective, following their plans to dominate the Balkans during the First and Second World Wars (Korinman, 1990), was in fact to dismantle Yugoslavia as early as the 1960s (Schmidt-Eenboom, 1995), with persistent support for separatist factions in Yugoslavia. During the Yugoslav crisis, Berlin unilaterally recognised Slovenia and Croatia in 1991, prompting other previously reluctant EEC members, particularly France (Stark 1992), to followsuit after this fait accompli. Berlin’s objective was to continue the dismantling of the spatial and geopolitical order resulting from the Treaty of Versailles, but under cover of the EEC and NATO. Indeed, the creation of Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia after the First World War had been promoted and supported by the United States, France, and the United Kingdom, in order to contain Germany in Central Europe and the Balkans. In Bosnia-Herzegovina, Washington, after supporting Yugoslav unity, changed its position and contributed to the torpedoing of the negotiations under the aegis of the Europeans. On 18 March 1992, the Bosnian Muslim leader Alia Izetbegović, encouraged by Washington, rejected the Carrington-Cutileiro plan (Republika Srepska. 2020) to continue the war against the Bosnian Serbs. Washington then supported a Muslim-Croat federation (Washington agreements in March 1994) against the Serbs of Bosnia-Herzegovina and Croatia, which aggravated the conflict and led to the Dayton agreements (1995). In Kosovo, the United States and NATO intervened to force Yugoslav troops to withdraw (1999). These successive interventions inaugurated a process of enlargement of NATO and the EU and thus an expansion of the Euro-Atlantic area into the former Yugoslavia under Washington’s direction. Croatia, Northern Macedonia, Montenegro, and Slovenia are now members of NATO. Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo aspire to membership, only Serbia has not applied to join NATO.

As far as Ukraine is concerned, the major factor in the conflict is also the attempt to extend the Euro-Atlantic space into the former USSR, particularly into Ukraine. From the point of view of geopolitical tropisms, for Germany, the objective of the Nazi regime was already to seize Ukraine (Franc 2018), as an extension of the Pangermanist plans to extend Germany’s Lebensraum (living space). Today, ideologies have changed but geopolitical focus on Ukraine is still present as the dominant view in Germany is that Ukraine should be westernised, i.e., oriented towards the Euro-Atlantic area according to German American priorities. For the United States, the objective is to detach Ukraine from Russia in accordance with the Brzezinski doctrine (Brzezinski 1995).

However, unlike the conflicts in the former Yugoslavia, Russia has once again become the central power in Eurasia and will no longer tolerate the unlimited expansion of the Euro-Atlantic area into its immediate neighbourhood (Finland and Sweden are already de facto part of the Euro-Atlantic area and were never part of the USSR).

Since NATO’s interventions in the Balkans and their consequences, the ex-nihilo creation of states such as Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo, played a fundamental role in the implementation of the unipolar spatial order, it is not surprising that they are taken as a reference in controversies about the war in Ukraine in relation to international law. Moscow’s reference to the NATO operation in Kosovo in 1999 serves as a mirror for the special military operation in Ukraine (Putin 2022). This argumentation accompanies the transition to a multipolar spatial and geopolitical order, superimposed on the unipolar spatial order that favoured the supremacy of the United States.

From a legal point of view, the crisis in Ukraine echoes the crisis in Kosovo, where a unilateral interpretation of international law was imposed by NATO member states. Today, as there is no agreement on the spatial and geopolitical order between the major powers, there can be no agreement on the interpretation of the international normative regime, according to the key idea of Carl Schmitt in his book The Nomos of the Earth (Schmitt 2012). In the absence of a multilateral consensus, there are only unilateral interpretations of the law. This legal no man’s land is above all the consequence of the unilateral interpretation, or non-compliance, with international law by the United States and its NATO allies during its previous crises: the NATO operation in Kosovo in 1999, but also the invasion of Iraq in 2003.

The principles of the United Nations Charter, the right of peoples to self-determination and the territorial integrity of states, have been instrumentalised to suit the geopolitical interests of the United States and its NATO allies during their period of world domination (the unipolar moment) following the demise of the USSR. Following NATO’s military operation against Yugoslavia, the United States made it clear that the principle of the territorial integrity of States did not prevent the secession of a territory in the case of Kosovo (International Court of Justice, 2009). Today, this argument logically reinforces Russia’s case for legitimising the border changes in Ukraine.

From the point of view of the war of communication, we can observe the same phenomenon of bias in the media of NATO member states, against the Russians in the case of the current conflict in Ukraine, and against the Serbs during the conflicts in former Yugoslavia (Republika Srepska. 2020). The history of the wars in former Yugoslavia needs to be rewritten, and this will also be the case for the conflict in Ukraine, because the non-explicit geopolitical issues are being glossed over and the media are producing biased narratives that do not reflect reality. The disinformation that has prevailed to this day, and which justified NATO’s intervention in former Yugoslavia, has not been called into question and is still the subject of an omerta of geopolitical realities in the Western media and academic world, apart from a few exceptions (Halimi, Rimbert 2019). More recent expert reports highlight the biased view of events in former Yugoslavia, which led to only one side, the Serbs, being blamed in a strategy of demonisation and ostracization that continues to this day (Republika Srepska. 2020).

Geo-historical legacies: the German question and the Serbian question

At the end of the First World War, Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, and Poland were promoted by the United States, France, and the United Kingdom as a belt to contain German power and prevent German expansion into Mitteleuropa and the Balkans. In 1938, the Munich Agreement led to the dismantling of Czechoslovakia and in 1940, Germany invaded Yugoslavia and supported the independence of Croatia. After the Second World War, Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia were again reconstituted, but under a communist regime. With German reunification in 1990, Czechoslovakia split into two parts (the Czech Republic and Slovakia), while Yugoslavia fragmented again between 1991 and 2006.

The remarkable geohistorical observation is as follows: each time Germany unified into a new state, Yugoslavia decomposed according to a principle of geopolitical communicating vessels. This is not a matter of chance, nor of any natural geopolitical occurrence. Berlin was involved in orchestrating the destruction of Yugoslavia in particular (Schmidt-Eenboom E 1995), in order to promote a fragmented spatial order more favourable to its geopolitical interests in Central Europe and the Balkans.

Any change of border is now considered unacceptable by NATO and EU member states. In fact, more than 15,000 km of new borders have emerged since the collapse of the USSR and the dissolution of Yugoslavia, while the geopolitical configuration is dynamic, and will probably lead to further border changes in the future. The member states of NATO approved these border changes because they corresponded to their geopolitical interests. However, they oppose the border changes provoked by Russia’s intervention in Ukraine, as well as Serbia’s rejection of the loss of Kosovo and the process of independence of the Serbian Republic of Bosnia. The meaning of history is also the reunification and unification of the historical territories of national entities. German reunification inaugurated the new dynamic in 1990, followed by the process of Russian reunification after the collapse of the USSR in 1991, with the return of Crimea to Russia in 2014, and then the Donbass and the territories of Novorussia in September 2022, each validated by a referendum . There is therefore no reason to deny this process to the Serbian nation, but the geopolitical obstacles remain, as this runs counter to the interests of the Washington/Berlin/NATO/EU Continuum (map 4: Border changes after 1989)

Border changes in Europe after 1989

Since 1989, more than 15,000 km of new borders have been erected. In European history, borders always changed and there has been no exception to this trend since the fall of Berlin Wall and for the future. In 1990, the German unification process was the first move of a huge transformation of European and Eurasian political geography. The German unification, in legal terms, was an annexation of German territory from former DDR into Western Germany (BRD) legal framework and constitution. After German unification, USSR dissolved itself in 1991 and provoked the biggest border change ever in Europe and Eurasia. The domino effect of geopolitical reconfiguration after the fall of the post 1945 order provoked both the peaceful break up of Czechoslovakia and the violent decomposition of Yugoslavia. It should be noted that both Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia were created as earlier as the First World war by allies to contain German power in Europe. After Germany’s revival as a united nation, these multinational state constructs disappeared as a geopolitical backlash of the new post Cold war order. The period from 1990 to 2008 has been characterized by the constant extension of Euro-Atlantic structures, NATO and EU in former Warsaw Pact members and former Soviet Union space. In 2008, the Russia-Georgia war could be qualified as the first war of the multipolar world. This new period till today is characterized by the geopolitical reconfiguration of the former soviet space with break up of States like Moldova, Georgia and Ukraine and the Russian nation unification.

Here is only described the evolution of regression and expansion of national territories, and the interpretation of the events in terms of international law is not debated here and subject to very deep disagreements between EU member states and Russia, but also within EU member states themselves.

In long term historical perspectives, the post Cold War era starting from 1990 till today was characterized by the national re-emergence and unification from both Germany and Russia, shifted in time, and with a geopolitical backlash provoking fragmentation of neighbouring states, putting a halt to Euro-Atlanticist exclusive dominance of the Eurasian space and leading to the multipolarization of Europe.

The unification /annexation of Crimea to Russia is only a step in these long-term geopolitical processes and we can expect more geopolitical rearrangement or decomposition of states, national territories, and international alliances as it was always the case in Europe through time.

The EU and NATO, obstacles to a fair settlement in the Balkans

Starting from the moment that NATO and the EU defend an exclusive Euro-Atlanticist spatial order stemming from the unipolar period since the collapse of the USSR and Yugoslavia, rejecting a multipolar world, the Balkan nations have no other choice but to vassalize their foreign policy in contrast to a multivectoral doctrine, according to the multipolar vision, which is refused to them. An equitable order is not possible either, since Serbia’s vocation is to conform to the priorities of the Euro-Atlantic order, and therefore to cut itself off from its traditional alliances, in particular Russia but also China.

Nor can the EU and NATO accept the dissolution of entities created to impose this new unipolar spatial order. To accept the dissolution of Bosnia, the result of the Dayton agreements, or of Kosovo, would mean the collapse of the whole EU and NATO narrative, plus two decades of policies in the Balkans aimed at enlarging this area and imposing the vision of liberal democracy.

The objective remains to push Russia and China out of the Balkans, as well as Turkey but to a lesser extent, because since it is part of NATO, its presence remains acceptable. Bosnia and Kosovo, the two artificial entities that NATO and the EU are seeking to crystallise, have as their main objective to weaken Serbia as an independent geopolitical entity and its historical link with Russia. Serbia and the Serbian Republic are on the front line between Washington/Brussels and Moscow.

The EU’s headlong rush towards enlargement to include Ukraine?

Against this backdrop, and opting for a headlong rush, Ukraine was granted EU candidate country status at the European summit on 23 June 2022, to anchor Ukraine to the Euro-Atlantic area in accordance with the vision of the spatial order of the unipolar period of US domination after the demise of the USSR. Yet Ukraine’s potential accession to the EU is a poisoned chalice. Yielding hastily to political promises such as the enlargement of the EU to include Ukraine and Moldova, or even Georgia and all the countries of the Eastern Partnership at a later date, will aggravate tensions and disappoint the people. Continuing the headlong rush towards enlargement will strengthen the geopolitical rivalry between France and Germany, further fragment the EU into rival sub-groups that risk being exploited by external powers, reinforce the division in favour of Washington’s hegemony and aggravate the systemic conflict with Russia. These enlargements are conceived as a manoeuvre to encircle Russia and China, not as a reinforcement of the European project, based on greater strategic independence and a reunification of European civilisation.

In the current balance of power, overcoming the Ukrainian question will require a partition of its territory and will constitute a major obstacle in the accession negotiations if the new borders and the attachment of the new territories to Russia are not recognised by the EU. What’s more, the EU as it operates today will not be able to absorb Ukraine because of the financial burden that it would entail. A far-reaching reform of the EU accompanying this enlargement would be dangerous because of the profound disagreements between states. Moreover, Kiev would seek to take advantage of its status as a Member State to torpedo any relations with Russia, further fracturing the EU between Poland and the Baltic States, which are the closest to the United States, and France, Germany, and Italy, which are keen to maintain links with Russia in the post-conflict period, as well as Hungary, which rejects sanctions.

This possible enlargement would reinforce the Franco-German geopolitical rivalry (Thomann 2022) because it would also accelerate a shift in the EU’s centre of gravity towards Germany and the east of the continent, absorbing funding to the detriment of Latin and Mediterranean Europe. The result would be to lock EU’s external relations into a systemic rivalry with Russia, in alignment with the interests of Washington and London and therefore to the detriment of the long-term priorities of Germany and France. The European political community initiated by Paris (Ministry of Europe and Foreign Affairs. France. 2022) undoubtedly has the implicit aim of slowing down the enlargement process or torpedoing it. Is the accession process stillborn and will it get bogged down as in the case of Turkey?

The main trend scenario is therefore for the situation to continue to worsen, with the future European and global space order at stake, hence the growing co-belligerence in support of Ukraine against Russia and under pressure from the military-industrial complex. The current conflict is taking on the dimensions of a systemic geopolitical conflict on a global scale between the promoters of the multipolar world (Russia, China, and the BRICS and Shanghai Cooperation Organisation members) and those who are seeking to slow down this development by clinging to the unipolar illusion (Washington/London/Brussels…), with a whole range of intermediate positions for the middle powers. This development goes against the interests of the peoples and nations of Europe in achieving greater stability, by leading the EU and NATO Member States towards Atlanticist priorities against Russia and China. This development means that the EU, rather than drifting towards a continental European area of cooperation, gradually extended to Eurasia, is instead drifting towards the status of a periphery of the Euro-Atlantic area dominated by the United States. How then can we limit the rise to extremes for Europeans who are located on one of the theatres of confrontation (the European Rimland)?

NATO’s enlargement to include the former USSR states is now a casus belli. Pushing Ukraine and Georgia into a bloc policy has turned these countries into frontline states rather than bridges for stabilising the continent. As a result, the buffer zones that are crucial to continental stability are the focus of destabilisation attempts that will affect the whole of Eurasia: the European Balkans, the Caucasian Balkans, Central Asia and Afghanistan, as well as the Mediterranean, the Black Sea and the Arctic, the rivalries between the major powers in these areas affect the security of the whole region.

The current conflict is taking on the dimensions of a systemic geopolitical conflict on a global scale between the promoters of the multipolar world (Russia, China, and the BRICS and Shanghai Cooperation Organisation members) and those who are seeking to slow down this development by clinging to the unipolar illusion (Washington/London/Brussels…), with a whole range of intermediate positions for the middle powers. This development goes against the interests of the peoples and nations of Europe in achieving greater stability, by leading the EU and NATO Member States towards Atlanticist priorities against Russia and China. This development means that the EU, rather than drifting towards a continental European area of cooperation, gradually extended to Eurasia, is instead drifting towards the status of a periphery of the Euro-Atlantic area dominated by the United States. How then can we limit the rise to extremes for Europeans who are located on one of the theatres of confrontation (the European Rimland)?

The main scenario of systemic geopolitical confrontation

The new emerging geopolitical configuration is characterised by uncertainty but will in any case be highly complex and fluid. Behind the term multipolar world lies a far more complex configuration than this geopolitical representation suggests. It is not a multipolarity resembling the concert of nations in nineteenth-century Europe, but a global fragmentation with different geopolitical orders competing not only in terms of geostrategy, but also in terms of values, the cement of the regional geopolitical order (Orford 2021). These spatial and geopolitical orders will compete and clash on the territory because their ideal territorial envelopes will overlap. With a fluid geopolitical situation on the horizon, there will be no respite from the fixed borders of the Cold War. The new confrontation between the powers in Europe could reawaken all the historical conflicts and disputes around Europe’s geographical perimeter. After the Black Sea and Ukraine, the Caucasus, the Balkans, North Africa, the Near and Middle East and the Arctic are likely to be destabilised in a highly dynamic process. At the same time, the multilateral system based on the geopolitical balances of 1945 (UN, OSCE, Council of Europe) and controlled by the Atlanticist West, because of disagreements between States, is increasingly inoperative, because it is based on an old spatial order that no longer exists (there is no acceptable international legal system between major powers without a spatial and geopolitical order).

If we think in terms of scenarios, we can identify two different trends for simplicity’s sake. The trend scenario (scenario 1).

is the continuation of a rise to extremes and the widening of the geopolitical conflict, with increasing cobelligerence (geostrategic and geo-economic) on the part of the States of the collective West, which are refusing the emergence of a multipolar world in order to weaken Russia. This process is leading to a deepening rift between the Atlanticist Western states and Russia and China, while the Global South and the Eurasian countries are coming closer together to build an alternative form of globalisation to the Americanised liberal West. These irreconcilable geopolitical rivalries are leading to a situation of permanent global conflict, affecting all areas of confrontation, and also causing fractures in Europe as the stakes increase. This scenario is the most dangerous, because the situation could slide into other high-intensity conflicts between major powers. A ceasefire or a temporary agreement on the Ukrainian question (partition of Ukraine as in Korea, a more or less frozen conflict) could also freeze the military situation precariously, but the war could reignite in the short to medium term because the pause would be used to rearm Ukraine.

If the NATO/Ukraine war against Russia were to escalate into a permanent systemic conflict, there would be a risk of spill-over into areas of confrontation in the Balkans, the Caucasus, the Middle East, North Africa, and the Sahel. Now in overdrive, the Washington/NATO/EU continuum in confrontation with Russia is putting pressure on European states such as Hungary and Serbia, but also on countries in Eurasia, Africa and South America that refuse to align with its geopolitical priorities. The result of this process is to fracture and destabilise Europe and its margins through the persistence of Washington/NATO/EU in seeking to impose a unipolar spatial and geopolitical order.

Washington/Brussels could seek to speed up the enlargement of the EU and NATO, with the aim of redirecting the candidate countries away from Russia and also China, since the EU is positioning itself as Rimland, as part of the US strategy of encircling Eurasia. The EU’s priority in the Western Balkans is to act in synergy with Washington and NATO to counter Russia, not to integrate Serbia, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo into a geopolitical strategy designed to make the EU an independent geopolitical power or to promote the strengthening/national renaissance of the candidate countries. However, the EU is likely to become increasingly divided on the question of enlargement to include Ukraine/Moldova, because the EU, as mentioned before, does not have the absorption capacity for the integration of Ukraine as it operates today. Because of the size of Ukraine’s territory (a territory larger than France) and its large (albeit shrinking) population, Ukraine would absorb a huge proportion of the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy and regional policy, and this would make negotiations between the Member States very difficult. However, before thinking about enlargement, given the current state of the conflict and the seemingly inevitable territorial partition of Ukraine, the recognition of new borders will have to be considered de facto or de jure, i.e., the acceptance of the attachment of Crimea, Donbass, and the oblasts of Zapozijia and Kherson to Russia. The example of Cyprus is a reminder that importing unresolved issues before joining the EU leads to blockages later on. Such a development could provoke a major diplomatic crisis with Turkey and the Western Balkan states, if Ukraine/Moldova were given priority for funding and the speed of enlargement negotiations, resulting in a blatant case of double standards. NATO, for its part, is very divided over the possible enlargement of NATO to include Ukraine (which territories? aggravating the casus belli with Russia).

What are the consequences for the Serbian world?

In this geopolitical context, do the Western Balkan states have a geopolitical interest in joining the EU, or even NATO? For countries such as Serbia and the Republika Srepska, (Bosnian Serb entity) which are neither in the EU nor NATO and are seeking to preserve their autonomy, the situation will inevitably become tense as considerable pressure will be put on them to choose sides. If Serbia seeks to join the EU, or even NATO, Belgrade would de facto be placed at the service of Euro-Atlantic priorities against Russia and China, while Turkey continues its entryism in the Balkans because it is a member of NATO and remains useful for destabilising Russia in the theatres where it is present (Balkans, Caucasus, Central Asia, etc.). There is a risk that the Balkans will once again become a theatre of hybrid wars between Russia and the United States and its allies. In the context of the current systemic geopolitical rivalries, Serbia risks losing its room for manoeuvre, and for the Republika Srepska within Bosnia-Herzegovina, the pressure would be even greater.

The current geopolitical situation in the Balkans is characterised by interlocking configurations, with a strategy of triple encirclement of Eurasia, the Western Balkans, and the Serbian world by NATO. As part of Washington’s grand strategy of encircling Eurasia and turning Europe into a Rimland against Russia, the geopolitical strategy of encircling the Western Balkans and Serbia by the Washington/Berlin/NATO/EU continuum continues at regional level. The aim of maintaining a united Bosnia-Herzegovina is simultaneously to detach the Republika Srpska from Serbia and, combined with Kosovo’s independence, to prevent the unification of the Serbian nation. This is in line with the German and American strategy of encircling Serbia to prevent Russia’s return to the Balkans. According to the scenario of increasing pressure and dominance from Washington/Berlin/NATO/EU, the ultimate objective is then to absorb the various states of the Western Balkans into the EU and NATO, once the policy of balkanising Yugoslavia has succeeded, after separating Montenegro from Serbia to cut off Serbia’s access to the sea. (map 5, Nato concentric and multi-scalar geopolitical encirclement strategy).

Brussels, supported by France and Germany (Euractiv 2022), is pushing for the normalisation of relations between Belgrade and Pristina, which would lead to the de facto recognition of Kosovo. The EU is also demanding that Belgrade apply sanctions against Russia, in order to cut off its historical links with Russia. The aim is also to distance the Republika Srpska from Serbia and Russia to torpedo any counterweight to the supremacy of Washington and its NATO allies. Serbia, which does over 60% of its trade with the EU, is being blackmailed into changing its alliances. This growing pressure could eventually lead to destabilisation and attempts at regime change.

Because of the priority given to Ukraine and Moldova for the so-called pre-accession funding programmes, but also for reconstruction in favour of Kiev, there is little interest for Serbia and Republika Srpska for joining the EU. In the EU as it functions today, Serbia and Bosnia-Herzegovina would only obtain the status of second-class member states (less funding but economic predation and societal colonisation by the EU (wokism, open society, no borders, immigration), very little political weight (no European commissioner, little weight in the Council and European Parliament, no important posts in the EU and transition periods to reduce funding and imports manufactured in Serbia). Investment from the EU risks being monopolised by an oligarchy and benefiting only a minority and would accelerate the destruction of the national economy in a process of economic colonisation that would see the country suffer a brain drain of graduates to the West (as in the central European states of the EU). Societal reforms (open society), as in the West, will dissolve Serbian identity in a process of westernisation that will lead to increasing cultural alienation.

Bosnia-Herzegovina (BIH) will never be a nation because the different entities represented cannot merge while preserving their very different geopolitical identities and mental maps. Bosnia-Herzegovina is an artificial state resulting from the dismantling of Yugoslavia. Once NATO members had fragmented Yugoslavia, in the name of the right of peoples to self-determination, there was no reason why the Bosnian Serbs should not be granted the same right, but Atlanticist geopolitical interests took precedence. The citizens of Republika Srepska have a legitimate right to self-determination.

As far as the process of national reunification or unification is concerned, the desire of the Russians in Donbass and the other entities of Novorussia to reunify with Russia and of the Bosnian Serbs to reunify with Serbia can be considered legitimate. However, the EU and NATO remain obstacles, even more so because the EU will lose all credit if the borders are changed and the artificially constructed entities in Bosnia/Kosovo collapse (European Council 2022a).

If Serbia and the Republika Srepska want to preserve their independence, it would be wiser to stay out of Euro-Atlantic alliances and pursue a policy of geopolitical balance and multi-faceted diplomacy. As an alternative, Serbia could promote multiple coalitions, bilateral or broader, with closer ties to certain countries, such as France, Germany, Italy, Austria or Hungary, depending on the objective to be achieved.

However, the danger is that NATO, as it can no longer be used as an offensive means of enlarging the Euro-Atlantic area could instead become very aggressive in areas under its control such as the Balkans. Russia is on the front line in Ukraine, and Washington and its NATO allies are seeking to open up other fronts against Moscow, in the Balkans in particular, but also in Georgia, Central Asia and the Middle East.

To favour the outcome most favourable to Europeans who wish to avoid the scenario of permanent conflict accelerating the EU’s drift towards peripheral status, we need to avoid a New Cold War and promote a new European geopolitical architecture, including Russia, which would be judicious for the European nations. (scenario 2)

A new European geopolitical architecture based on the new spatial order

A different scenario is one in which Russia emerges even stronger from the conflict against Kiev, supported by NATO, in the context of a rise in power of non-NATO states that wish to do away with the old order. Faced with a growing inability to prevent the inevitable emergence of a multicentric world, Washington, and its NATO/EU allies, instead of taking increasingly destabilising action, would be de facto forced to accept the multipolarisation of the world and stop raising the stakes, particularly because of the nuclear risk (scenario 2). This scenario would be favoured, for example, by the possible reduction in Washington’s aid to Ukraine with the return of the Republicans in the American elections. This is the only scenario, although unlikely today, that could lead to relative stability, albeit precarious and temporary. According to this scenario, Serbia and the Republika Srpska have no interest in joining the EU either, which would also be weakened, unless there is a drastic reform of the way it works as well as its paradigms, which is today unlikely. Outside EU Serbia and Republika Srpska would then take advantage of a better European and global geopolitical balance to preserve a multi-faceted diplomacy, especially by preserving their links with Russia, but also with China.

Let us remember that the international system today is a struggle to distribute geopolitical spaces. As Raymond Aron has pointed out (Aron 1962), any international order is necessarily a spatial (and therefore geopolitical) order. A new spatial order is emerging, reminiscent of the Grossraum described by Carl Schmitt, which structures international space (Schmitt 2012). The whole of Europe and its geographical proximity risk being the theatre of permanent confrontation and all the frozen conflicts could escalate. It is an illusion to think that every regional conflict in Europe and Eurasia can be resolved on a case-by-case basis, because they are all interlinked, and their resolution depends on the acceptance of a new spatial and geopolitical order. The condition for a shared interpretation of international law by the major powers is to reach at least a temporary and precarious agreement on the spatial and geopolitical order between them. It is therefore a systemic approach on a continental scale that would be judicious, opening the way to a new Eurasian geopolitical architecture that would be the key and the condition for the stability of the whole.

The European project faces some drastic choices in the longer term: can the EU confine itself as it does today to playing the role of Rimland in the strategy of the United States and rearm against Russia without any independent geopolitical strategy, as proposed by Josep Borell, head of the EU’s external service (Borell 2023)? This suits some NATO member states, but it will lead to an arms race and a lasting European fracture with the emergence of the Washington-London-Brussels-Warsaw-Kiev axis and a loss of influence of the Franco-German axis and the strengthening of Franco-German geopolitical rivalry (Thomann 2022). Russia, for its part, will pursue its project for a greater Eurasia, and its pivot towards Asia will accelerate. Russia’s geo-economic reorientation and changing alliances on a global scale are in its favour, with the EU being the big loser.

A New European Geopolitical Architecture and the pivot to Russia

According to an alternative scenario, it is up to the Europeans to try to re-engage with Russia in the post-conflict period, as Russia will remain a geographical neighbour of the EU. In reality, Russia and Western Europe are inseparable, both geographically and in terms of civilisation. A geopolitical Europe can only reach a minimum threshold of power with Russia. A Europe cut off from its eastern flank will remain no more than a periphery of the Euro-Atlantic area under Washington’s domination.

The idea is to relaunch a « Greater Europe » to position Europeans between a « Greater West » centred on the United States and its « America First » doctrine, China’s « Greater Asia/New Silk Roads » project, and Russia’s « Greater Eurasia » project, the heart of which is the Eurasian Union. These initiatives will overlap, often competing, but sometimes complementing each other. Europeans must not remain inactive in the face of the great manoeuvres of other powers. A reformed EU and Russia can avoid becoming junior partners in these rival geopolitical projects, with the EU remaining a peripheral sub-element of the « Greater West » and Russia a sub-element of the « Greater Asia ». To avoid the status of periphery, it would be in the interests of the Germans and the French to promote a large area of cooperation, stability, and prosperity in the depths of Eurasia, which is becoming the centre of gravity of a globalisation alternative to Western globalisation, without rejecting any of the major evolving groupings. This means working in synergy with Russia’s Greater Eurasia project and China’s Silk Roads. By reintegrating Russia into the strategic plans, the manoeuvre would have the dual advantage of ensuring greater security for Europeans by altering external balances and addressing the EU’s internal imbalances after Brexit. The current global and European geopolitical configuration lends itself to the anticipations of General de Gaulle, who envisaged a « Europe from the Atlantic to the Urals » based on states and nations once Russia had emerged from communism. Europeans should avoid being seen as second-rate players to be divided or enlisted in the American-Russian rivalry (map 6: New European geopolitical architecture: for a better European, Eurasian, and global balance).

But this option requires overcoming the crisis in Ukraine.

The rift with Russia is not irremediable in the longer term in a geopolitical configuration that is evolving very rapidly, where alliances are becoming more precarious and temporary depending on national interests and crises.

The Greater Eurasia project has never excluded the Europeans (Glaser (Kukartseva. Thomann. 2021), and Vladimir Putin’s speech underlined that the Russians remain open to cooperation with the traditional West (Putin 2022), but on condition that Russia’s security interests are taken into account in accordance with the principle of the indivisibility of security. A better geopolitical balance in Europe is needed to avoid the hegemony of Washington, which is dragging Europeans into conflicts with Russia and China, to the detriment of the national interests of many states and to the sole benefit of the supremacist vision of the neo-conservatives in Washington and the NATO/EU-aligned bureaucracies. Balance does not mean neutrality but counterbalancing an overly dominant pole with another pole of balance. The central challenge for the future is therefore to find a way of containing conflicts in the areas of friction between these hierarchical regional alliances, characterised by a centre and a periphery. The main challenge will be to set limits to the continued expansion of the West under Washington’s leadership, which is seeking to impose an exclusive Euro-Atlantic order in Europe, right up to Russia’s borders and in the Balkans.

Paradoxically, negotiating with Russia might become easier once NATO enlargement ceases, Ukraine’s de facto neutralization occurs, and Ukraine’s partition gains acceptance from all parties since the boundaries of alliances would have been clearly drawn in accordance with the principle of the indivisibility of European security. There is no Russian threat to the EU’s borders, the conflict is confined to Ukraine because Russia’s priority is its near abroad (the former USSR apart from the Baltic States).

A better geopolitical balance in Europe is needed to avoid the hegemony of Washington, which is dragging Europeans into conflicts with Russia and China, to the detriment of the national interests of many states and to the sole benefit of the supremacist vision of the neo-conservatives in Washington and the NATO/EU-aligned bureaucracies. Balance does not mean neutrality but counterbalancing an overly dominant pole with another pole of balance. The central challenge for the future is therefore to find a way of containing conflicts in the areas of friction between these hierarchical regional alliances, characterised by a centre and a periphery. The main challenge will be to set limits to the continued expansion of the West under Washington’s leadership, which is seeking to impose an exclusive Euro-Atlantic order in Europe, right up to Russia’s borders and in the Balkans.

Rebalancing the Franco-German axis in favour of Paris through closer ties with Russia and the Serbian world in the Balkans

At the heart of the European project lies Germany, which sees itself as a central power, and France, a balancing power. The two nations oscillate between rivalry and cooperation in the « Franco-German couple ».

The new Franco-German geopolitical rivalry over European goals (Thomann 2015) is the epicentre of the EU crisis, with a growing asymmetry between the two countries to the advantage of Germany as the central power. Germany has consolidated its position as the EU’s geopolitical centre of gravity since reunification and successive enlargements. Since the crisis in Ukraine, the rivalry between Paris and Berlin on defence issues has also intensified (Thomann 2022). Faced with the new global configuration, it would be wise for France to adopt a new geopolitical stance[viii]. This shift involves reevaluating geopolitical priorities and alliances while abandoning any illusions regarding Europe’s role integrated into the EU to balance Germany and obtain a privileged position within an alliance with the Anglo-Saxons. The AUKUS alliance in the Indo-Pacific, in which France was sidelined, has shown that this was an illusion. For France, exploiting the potential offered by its geography suggests positioning itself as a pole of power and a balancing factor at the hinge of the Euro-Atlantic, Euro-Asian, Euro-Mediterranean, African, and Euro-Arctic geopolitical spaces.

The main theatre for France remains Europe, its Eurasian hinterland (Russia, Turkey, Caucasus, Central Asia), its Euro-Mediterranean hinterland (Maghreb/Sahel, Near and Middle East) due to geography and alliances (EU-NATO) and he Indo-Pacific area.

What are the options for France and its European partners in this changing configuration?

To re-establish the Franco-German geopolitical balance, it is once again the continental vision inspired by Gaullism that would be relevant for France to regain its strategic autonomy in a Europe of nation states. As we have said, a rebalancing of the exclusive Euro-Atlantic project cannot be effective without a change of scale in the European project, from Brest to Vladivostok, in other words a rapprochement with Russia.

Since the EU and NATO, without drastic reforms, are no longer in a position to enable France to regain its role as a balancing power according to General de Gaulle’s vision, it would be wise for Paris to renew its ties with its historic alliances, Russia and Serbia (and the Serbian world) to balance the German-American EU.

After years of abandoning and dissolving its historical links with the Balkans, due to an alignment with an exclusive Franco-German couple, but increasingly asymmetrical in favour of Berlin and exclusive Euro-Atlanticism in a German-American Europe, it would be in France’s interest, according to a revival of the notion of a balancing power, to reconnect with the Serbian world, today split between Serbia, the Serbian Republic of Bosnia and Kosovo, in order to promote a better geopolitical balance in the Balkans, but also in Europe and the world.

On a global scale, the main new manoeuvre would be to avoid France and its European partners becoming embroiled in a head-on American-Russian and American-Chinese rivalry and locked in between the two arcs of crises in its geographical proximity to the South (from the Sahel to Afghanistan) and the East (from the Arctic Ocean to the Black Sea). To loosen this stranglehold, forcing Europeans to act on several fronts simultaneously and draining their resources, a pivot towards Russia would be an appropriate strategic manoeuvre. Russia is not a threat, either to France or to the Serbian world, despite NATO’s attempts to engage in a new Cold War that is dangerously fragmenting Europe. The most appropriate scenario for greater strategic autonomy for France and the Europeans would be to play a moderating role with Russia in the growing global confrontation between the United States and China. This would avoid Europeans being subjected to a form of US/China condominium marginalising the EU and Russia in world affairs. The states that, in the recent past, have been most in favour of a rapprochement with Russia are France, Germany and Italy, who could be the pillars of such an initiative along with other Member States such as Austria, Belgium, Luxembourg, Spain, Portugal, Hungary, Greece and Cyprus, but outside the EU, Serbia.

The pivotal role of France and Germany at the heart of the EU remains central, particularly on economic and monetary issues. However, a rebalancing is needed with the countries of the Latin arc, such as Italy, Spain and Portugal, with regard to the management of the euro, the countries of Central Europe with regard to the preservation of the values of European civilisation, and also outside the EU, the states and entities of the Serbian world, to counterbalance the excessive weight of Germany, the United States and the United Kingdom (since the Brexit, London has returned to its objective of strengthening NATO against Russia and fragmenting the European continent in unison with Washington) on foreign policy issues.

A new stable European order based on a new spatial and geopolitical order outside NATO?

If Europeans try to re-engage with Russia in the post-conflict period, it will be difficult if not impossible to do so through NATO, but also through the EU if it is not reformed, because the member states are very divided on the issue. The Euro-Atlantic geopolitical order, which is exclusive, is obsolete for promoting continental security. The outcome of the conflict in Ukraine is uncertain, but it is clear there will be no turning back, as the global geopolitical shift towards a multicentric world has accelerated once and for all. Enlargement of NATO and the EU is probably impossible in Russia’s near abroad, and the EU and NATO will no longer be able to structure the spatial and geopolitical order of the Eurasian continent. The idea of a new European geopolitical architecture with Russia could be based on more solid foundations with the model of a Europe of sovereign nations and the principle of geopolitical balance. The concept of a more balanced security for all the nations of the European and Eurasian continent could replace NATO’s doctrine of expansion as a central and priority condition for stabilising Europe. Ultimately, it is also a question of rediscovering the classic negotiations on European, Eurasian, and global balances (map 6: New European geopolitical architecture: for a better European, Eurasian and global balance).

With the crisis in Ukraine, the EU has suddenly changed its narrative from one focused on peace to one of war against Russia, but without a coherent geopolitical strategy or a crisis exit plan based on geopolitical realities rather than ideology. The foundations of the European project need to be reformed. The reformed European institutions and European governments should free themselves from the currently dominant ideological reading grid analysing international situations according to the simplistic opposition between democracy and dictatorship, focusing on human rights according to the ideological multiculturalism aligned with the narrative of the Washington neoconservatives. To establish a correct diagnosis of the world, the reality of national identities, the geographical position of states, their geopolitical perceptions including the long history of territorial envelopes and civilisations should be better taken into account. Each nation has the right to develop its own model and there is no supreme judge to determine the ideal model of society and democracy.

This new spatial order, as the basis for a new European geopolitical architecture, would ideally include the following elements: a clearer delineation of reciprocal red lines, the neutralisation of buffer states, the negotiation of the geographical limits of alliances, and the avoidance of the installation of offensive military infrastructures on border territories. In the longer term, assuming a return to mutual trust, this new order would go as far as identifying common geopolitical interests such as stabilising the crisis arc south of the Mediterranean as far as Afghanistan, the fight against jihadism, the energy issue, social inequalities and a new development model, migration, the environment, and the challenge of artificial intelligence.

A new geopolitical architecture would not necessarily take the form of new formal treaties on European security since the major powers do not currently have the same vision of the new spatial and geopolitical order. Failing this ideal option, which could nevertheless be promoted in the longer term, this new space order could emerge in a non-explicit manner, without legal formalisation. It would therefore imply a de facto halt to the expansion of both NATO and the EU, a « neutralisation » (neither NATO nor the EU) of Ukraine and the states of the former USSR, the identification of states’ red lines and the negotiation of zones of influence. The disagreements between Turkey and the EU over Cyprus are an example where these incompatibilities do not prevent cooperation on other issues. A way out of the crisis could therefore be facilitated first and foremost by the sending of signals by European states wishing to stabilise the situation and promising to engage in long-term negotiations with Russia. Of course, this objective is extremely difficult in the current configuration, but it is the process of gradually reducing tensions and regaining mutual trust that is most important, even without immediately arriving at a new arrangement. In a geopolitical Europe, like the world and Europe’s long history, treaties are in any case only precarious and temporary, and have never fixed geopolitical configurations that inevitably evolve.

The geopolitical future lies in overlapping cooperation axis.

The promotion of a Paris-Berlin-Moscow axis, to balance the Washington-London-Brussels-Warsaw-Kiev axis, would also have to coexist with the Washington-Paris-Berlin axis and the Moscow-Beijing axis. Superimposed on the emerging new spatial order is the multilateral framework, i.e., the international organisations that accompany and stabilise the geopolitical order. Acceptance of the new multipolarity is inevitable. As we have said, once the crisis is over, the necessary stabilisation of the European continent does not necessarily involve the EU and NATO, organisations that reflect and are based on a spatial order linked to the exclusive Euro-Atlanticism that emerged from the Cold War and the unipolar world that led us to the current crisis. The most effective solution would lie in a new arrangement outside the NATO/EU institutions, with smaller and more variable coalitions of states, and why not the creation of new, more appropriate structures. It would also be essential to re-found the European project and reform the EU accordingly, as its current form is obsolete: maintain the EU as an international organisation on the single market but abandon its supranational and federal drift and question its complementarity with NATO.

Once an agreed balance of power between great powers leads to better stabilization, from the multilateral angle at global level, the idea would be to connect international organisations, such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, the BRICS, the Collective Security Treaty Organisation with the EU, NATO, the Council of Europe and the OSCE, and to reinvest the UN. The main challenge is to resolve the issue of the missing link in European security, which is a necessary step towards a Eurasian area of stability and cooperation at continental level, which means innovating and inventing new multilateral organisations on a continental scale to stabilise this immense area. Russia is no longer a member of the Council of Europe and it would be useful to create a new continental organisation with Russia, but based on paradigms other than the westernisation of Russia (map 7: « overlapping circles of world stability » – « rose window of cooperation »).

If the scenario of a de facto acceptance of multipolarity by the Washington/Brussels continuum materialises, like France according to Gaullist vision, the Serbian world would also benefit from the prospect of a new European geopolitical architecture, based on the vision of a Europe of nations, as an alternative to integration into the Euro-Atlantic system in crisis. In this configuration, the various fragmented entities of the Serbian world – Serbia, Republika Srbska and the Serbs of Kosovo – would have more room for manoeuvre to draw closer together, or even reunite, in the same way as other major European nations such as Germany and Russia. This stabilisation is the alternative to a situation of permanent conflict in all areas of confrontation, which is particularly unfavourable to Europeans, but less so to Americans on the other side of the Atlantic. The central issue for Europeans, motivated by greater independence, is to become independant from Washington. This halt to the spiral of conflict could ideally lead to a new long-term security treaty, once a new generation of politicians have come to power, because the current leaders are too committed to irreconcilable positions. The worsening of the crisis in the foundations of the current space order may well be the spur needed for innovative geopolitical solutions.

The missing link in European security

To promote continental stability, it would be wise to imagine the cohabitation of several geopolitical envelopes. The aim would be to avoid open conflict, and thus promote relative stability between states. Without building their own geopolitical strategy independently of the United States, the Germans and the French and their European partners will not be able to carry any weight in the world and will not be seen as reliable partners for Russia, which rightly considers that they are aligned with the geopolitical priorities of the United States.

The future lies in complexity, in the superposition of geopolitical projects, in their articulation to preserve stability and geopolitical balance. Constructive multiplicity will be the key to the new Europe, with a reaffirmation of the Westphalian principles of the world that have been undermined by the globalist project of the Euro-Atlantic institutions (EU and NATO). The return of the notion of balance between powers is necessary to manage geopolitical entanglements, but also the notion of a large geopolitical space on a continental scale to defend the common elements of European civilisation between European nations and other geopolitical spaces, in particular civilisation states.

The control of territories is central to the new configuration of the struggle to distribute geopolitical spaces. To stabilise the situation, a new spatial order is needed, to pave the way for a new legal order, which will be based on more solid geopolitical foundations.

This conflict is therefore an opportunity to re-establish a spatial and legal order to limit conflict. Otherwise, instability will continue, and the conflict will be latent, or even frozen, with no prospect of resolution.

Over and above these considerations, it is clear that if this new spatial order is to be accepted, the United States and its Western allies must accept the multipolar world as a precondition (the West defined as all the states covered by the global protectorate of the United States, i.e. a notion born of the Cold War). The stability of Europe will depend on the ability to take into account the security interests of all countries, including Russia, and to establish a new European order based on the principle of the indivisibility of European security and not exclusively that of NATO members to the detriment of Russia, which emerged from the disappearance of the USSR.

Conclusion

The emerging new geopolitical configuration is still uncertain but will in any case be highly complex and fluid. There can be no functional international law without a geopolitical spatial order, so today, as the spatial order is changing, a new architecture must be renegotiated on the scale of the European and Eurasian continent, a space of security, prosperity, and cooperation, in phase with the historical space of European civilisation. The challenge is not to let others dictate the paradigms of thought, the diagnosis, and the priorities of other players, whether allies or adversaries, in order to promote our vision of the world and our desired place in it. In other words, it is the one with the initiative who imposes geopolitical changes. To adopt a geopolitical strategy, we need to position ourselves at the centre of the map and project ourselves into different spaces: land, sea, air, but also space, cyberspace, digital space, and the space-time of artificial intelligence.

Geopolitical Europe could become the renewed goal of the European project and be promoted by a coalition that is in favour of a better geopolitical balance like France and Serbia. It is defined here as an alliance of European states seeking autonomy of thought, decision, and action at the international level in order to ensure their security, defend their strategic and vital interests, and promote the conditions for the flourishing of their common civilisation. It does not, therefore, aim to « merge » the Member States. Intergovernmental decision-making would be the preferred way of deciding on joint actions, making the most of the cumulative synergy of different sovereignties, rather than sharing sovereignty, which turns out to be a division of sovereignty. Europeanised issues must be shared in a way that is agreed and controlled by the Member States, which remain the masters of the Treaties.

If it is to survive, the European project needs to change scale, but this means identifying obstacles and opportunities and identifying common interests. The three main challenges can be summed up as follows: regaining control of the territory, halting the demographic collapse, and preserving the common features of European civilisation. All these challenges can only be tackled on the right scale, the continental scale, including the geographical proximities adjacent to the Eurasian continent. The need for a new European security architecture with Russia is also essential for Europe’s stability. The Franco-German pairing is too weak in Europe, and it needs to change scale and include Russia, in particular to position itself in the background of the growing rivalry between China and the United States and avoid a Sino-American G2 (map 6: New European geopolitical architecture: for a better European, Eurasian and global balance).

The most likely scenario is a further escalation of the conflict in Ukraine and the proliferation of major crises looming on the horizon and awaiting Europeans on a scale not seen since the Second World War. The economic and political consequences of the crisis in the foundations of the obsolete world and European order have probably not yet reached people deeply enough for the political class to take decisions commensurate with the challenges. However, the crisis in Ukraine must first be overcome. It is now necessary to consider alternative scenarios in the context of a geopolitically more fluid world characterised by a proliferation of strategic surprises.

The priority is to avoid a new Cold War, which is the project of the promoters of exclusive Euro-Atlanticism. In order to overcome the Ukrainian crisis, which has become hostage to American-Russian rivalry, and to engage in negotiations, the prospects of a Franco-German-Russian rapprochement on geostrategic and geo-economic issues could help to convince Russia to commit itself to new security guarantees that include all European states, based on the principle of the indivisibility of security and on the acceptance of a new spatial order, Western Europe, Central and Eastern Europe and the Balkans, in order to overcome the fracture at the heart of Europe.

The future obviously depends on the conflict in Ukraine and whether or not Russia emerges strengthened, a precondition for a return to the Balkans from a position of strength. Elections in the United States and the EU, such as in France, where opposition parties will be more in favour of Serbia and less in favour of NATO/EU, are also factors to be taken into account.

References

Arms control association (2022), Russia, U.S., NATO Security Proposals https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2022-03/news/russia-us-nato-security-proposals

Aron R. (1962), Peace and war between nations. (Paix et guerre entre les nations), Calman-Levy, 2004, p. 187

Borell J. (2023), Lessons from the war in Ukraine for the future of EU defence, https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/lessons-war-ukraine-future-eu-defence_en

Brzezinski Z. (1997). The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and Its Geostrategic Imperatives ( (French version : Le grand échiquier, l’Amérique et le reste du monde), Bayard 1997, 275 p

Cour internationale de Justice. (2009). https://www.google.com/search?q=www.icj-icc.org+Kosovo+Question+pos%C3%A9e+par+M.+le+juge+Koroma+Il+a+%C3%A9t%C3%A9+affirm%C3%A9+que&client=firefox-b-d&sxsrf=ALiCzsbYDDHKp9u4S4zAJ85zqoZI1DHB_A%3A1665324042857&ei=CtRCY_nuM6zikgW00JKoCw&ved=0ahUKEwj5m4rAp9P6AhUssaQKHTSoBLUQ4dUDCA0&uact=5&oq=www.icj-icc.org+Kosovo+Question+pos%C3%A9e+par+M.+le+juge+Koroma+Il+a+%C3%A9t%C3%A9+affirm%C3%A9+que&gs_lcp=Cgdnd3Mtd2l6EAM6CggAEEcQ1gQQsAM6BQgAEKIEOgcIABAeEKIESgQIQRgASgQIRhgAUKEGWLEQYM0XaAFwAXgAgAGqAYgBkAKSAQMwLjKYAQCgAQGgAQLIAQjAAQE&sclient=gws-wiz

Die Zeit (2022). Did you think I would come with a ponytail? (Hatten Sie gedacht, ich komme mit Pferdeschwanz? ) Angela Merkel interview, 7 december 2022. https://www.zeit.de/2022/51/angela-merkel-russland-fluechtlingskrise-bundeskanzler/komplettansicht

European Conservatives and Reformists group (ECR), European Parliament, (2023),

ECR Foreign Affairs Coordinator Anna Fotyga, together with ECR MEP Kosma Złotowski, hosted in the European Parliament, the conference ‘Imperial Russia: Conquest, Genocide and Colonisation. Prospects for Deimperialisation and Decolonisation’, Tuesday 31 January 2023, https://ecrgroup.eu/event/the_imperial_russia_conquer_genocide_colonisation

European parliament (2019), European Parliament resolution of 12 March 2019 on the state of EU-Russia political relations, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-8-2019-0157_EN.html

Euractiv (2022), Macron, Scholz’s aides head to Belgrade, Pristina in new diplomatic push, https://www.euractiv.com/section/politics/short_news/macron-scholzs-aides-head-to-belgrade-pristina-in-new-diplomatic-push/

European Council (2022a), Political agreement on principles for ensuring a functional Bosnia and Herzegovina that advances on the European path, https://www.pressclub.be/press-releases/european-council-political-agreement-on-principles-for-ensuring-a-functional-bosnia-and-herzegovina-that-advances-on-the-european-path/

European Council, (2022b), A Strategic Compass for a stronger EU security and defence in the next decade, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/fr/press/press-releases/2022/03/21/a-strategic-compass-for-a-stronger-eu-security-and-defence-in-the-next-decade/

Financial times (2023), France, Germany and Poland vow long-term support for Ukraine, https://www.ft.com/content/7a02008d-adbd-4940-9d43-821dc93a6fca

Florian L. ( 2014). The great theorists of geopolitics. (les grands théoriciens de la géopolitique), Belin, 2014

Franc C. (2018). Histoire militaire – Le Traité de Brest-Litowsk : ses clauses et ses conséquences. Revue Défense Nationale 2018/2 (N° 807), pages 121 à 123 https://www.cairn.info/revue-defense-nationale-2018-2-page-121.htm

Foucher Michel (2011) La bataille des cartes, Analyse critique des visions du monde, 2011, 192p